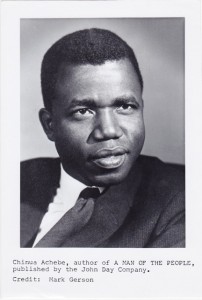

Chinua Achebe

KURT THOMETZ

NEW YORK CITY

Things Falling Together

On Saturday, May 4, the great Nigerian author Chinua Achebe spoke at NYU’s Vanderbilt Hall. It was an elegant venue for the man who is arguably the greatest literary stylist of the second half of the 20th Century (Things Fall Apart, A Man of the People, Anthills of the Savannah) and one of the very few truly wise people I have ever met. The evening was co-hosted by NYU’s Institute of African-American Affairs and Department of Africana Studies with MoMA to mark the end of P.S.1’s Okwui Enwezor exhibition, “The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945-1994.”

Achebe reflected on this topic in his remarks.

“In 1957, Ghana was independent. It was as if the whole of Africa were on fire. Accra [Ghana’s capital] is one hour behind Nigeria. Midnight in Accra was 1 a.m. in Lagos. Everybody in Lagos was awake. No tv but tuned into what was. E.T. Mensah wrote a highlife [song], ‘We will be happy and gay on Independence Day.’ Everybody was jumping.”

Where highlife, the dance-pop music of Nigeria and Ghana that was at its height from the 1950s through the 60s, describes West African modernity in (old) rhythm and (new) blues, Achebe defines “the reality here on the ground” by age-old Igbo proverbs and swings its ecclesiastical responsibilities. He might be called the ace in the house of cards that is Nigeria. “I had to write on the chaos I foresaw,” he explains. In the turbulent and often bloody political environment of post-colonial Nigeria, this has taken an incredible amount of courage. It has been a bitch. During the Biafran War his apartment was bombed. There are people who will tell you the 1990 automobile wreck on the Onitsha-Enugu road that left Achebe paralyzed from the waist down was no accident. Truth has consequences.

In Things Fall Apart (1958), the existential dilemma that is Nigeria and is Africa is also modernism’s heart of darkness. As Manthia Diawara (director of NYU’s Africana Studies department) pointed out this evening, Conrad described it, but Achebe defined it as only an artist can. Achebe refracts modernism’s destructivist ethics. His voice cautions against presumption, against ignorance, against ill-thought obedience, and for the humanism born of print on paper.

Things Fall Apart also measures the change in consciousness effected by the age-old oral world ceding to literacy in Africa. In 1958, Things Fall Apart was published to no fanfare. Nigerian literature at the time consisted of the writers associated with the Onitsha Market, an indigenous phenomenon, and Amos Tutuola’s intoxicating The Palm-Wine Drinkard and My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. It came preciously near being overlooked. Today it is taught not only as literature but as history, anthropology, and a primer in communications theory.

Things Fall Apart also measures the change in consciousness effected by the age-old oral world ceding to literacy in Africa. In 1958, Things Fall Apart was published to no fanfare. Nigerian literature at the time consisted of the writers associated with the Onitsha Market, an indigenous phenomenon, and Amos Tutuola’s intoxicating The Palm-Wine Drinkard and My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. It came preciously near being overlooked. Today it is taught not only as literature but as history, anthropology, and a primer in communications theory.

In The Gutenberg Galaxy, McLuhan, an early Western appreciator of the new Nigerian literature, refers his readers to it as a way toward grasping the consequences of the change in media that Things Fall Apart chronicles. The gangster/tyrant Sani Abacha, who ruled Nigeria for much of the 90s, seems to have accomplished post-literacy before most Western leaders did-though George Bush seems closer to succeeding in facilitating the same transition here than I am comfortable with. Whether the White House’s planned “listening tour” of black Africa, indefinitely postponed when the sky fell on September 11, would have been anything more than a camera safari is unlikely.

“Africa is in a bad way,” Achebe told us. “The reason is not Africans. The Cold War did more damage in Africa than any other continent. It was split down the center. Our chances were limited by the powers. Now, that is out of the way and nobody is talking about it and nobody is talking about Africa.”

The root of Africa’s suffering of modernity is in the corruption of First World presumptions and vested interests that it’s been Achebe’s mission to address. The more you read of and about him, the more respectful you become of his deportment, his stature, his cool, and above all his message. This night he read an excerpt from Things Fall Apart, poems from Beware Soul Brother and a limerick he wrote in college-telling its story in a way that in lesser hands might have come off rather precious. Instead it is ennobled, as the very African esthetic of cool always does.

His reader gathers an egalitarian quotient from the timbre and tone of dry irony in the Igbo language, which underlies Achebe’s English literature and voice. It takes us back to the fundamentals, when words were magic, had mysterious powers, and what you wanted to happen could by your saying it. It is a praise song to print’s capacity to bring hidden wisdoms within our grasp. Achebe reminds us things are not what they seem, and no condition is permanent.

Kurt Thometz is the editor/author of Life Turns Man Up and Down: High Life, Useful Advice, and Mad English.

Volume 15, Issue 20

© 2006 New York Press

For more on Chinua Achebe, see the Learner project.

Jumel Terrace B&B

Jumel Terrace B&B Life Turns Man Up & Down

Life Turns Man Up & Down The Private Library

The Private Library