From the Library of Diana Vreeland

“Let’s suppose you were a total stranger – and a very good friend. That’s a good combination. What would you want to know about me? And how would you go about finding it out? To me the books I’ve read are the gateway. My life has been more influenced by books than by any other one thing.”

-Diana Vreeland, D.V. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984)

The first house call I made to care for an ailing library, which came first to be something of a sideline, later an occupation, was more of a blind date than a job. Of the doyenne of American fashion, the enfant terrible of magazine editing whose every bon mot seemed to bare repeating, whose reputation inspired emulation by society girls, the veneration of artists, and adoring imitation by drag queens, I hadn’t expected great bibliophily.

“From the time I got married at eighteen until the time I went to work in 1937, twelve years – I read. And Reed [Vreeland] and I would read things together out loud, which was marvelous. That was the charm of it – when you’ve heard the word, it means so much more than if you’ve only seen it.”

Her library had surrendered to chaos through constant use and to put your hand to what you wanted – unless you could follow the Zen logic imposed by a pot-headed friend of her grandson – was difficult and ineffectual. Cataracts, which would eventually blind her to the written word, were making disorder too difficult to be practical. Christopher Hemphill, her co-author, was a friend and effected our introduction and my first job as a private librarian.

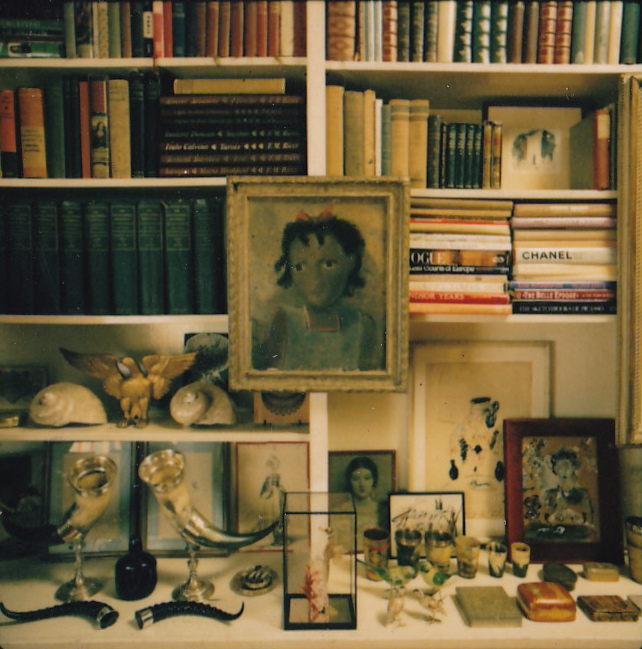

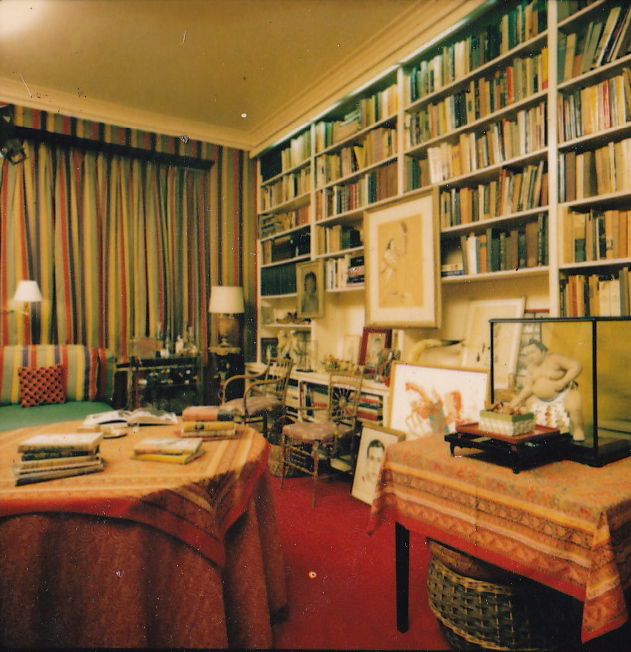

The apartment was Billy Baldwin’s famous interpretation of Mrs. Vreeland’s dictate to furnish her flat like “a garden in hell.” Scarlet fleurs du mal chintz covers everything in the living room, red wall to wall underfoot: a seascape of shells, Venetian blackamoors, a Sumu wrestler under glass, Warhol’s lithograph of Mrs. Vreeland as Napoleon, two Christian Berard portraits of her as a working editor, a Zuloaga scene of Easter Sunday in Seville, and a Dufy watercolor of a Venetian canal.

While she loved Venice she preferred Bahia, thought Salvador more beautiful, and the most charming picture she owned was a primitive portrait of a girl I loved. Where books weren’t, bibelots adorned every available surface: Scottish horn snuffboxes, a kennel of Staffordshire dogs from her late husband, porcelain leopards given her by Jean Schlumberger. Nothing priceless in itself but invaluable by association.

In my categorizing and arranging I was drawing a bibliographic portrait of Mrs. Vreeland and falling a little bit in love despite our fifty year difference in age. Her library possessed what Cecil Beaton characterized as her “most strict sense of chic and a poetical quality quite unexpected in the world of tough elegance in which she works.” This exacting sensibility distinguished her books as a collection, as opposed to a mere accumulation. Most of the books were by her contemporaries, coincidentally first editions, many gifts respectably inscribed by their authors. Condition didn’t interest her. The books were dog-eared, underlined, spines faded, jackets torn and well worn, not just read but reread.

The effete elite from past to present, rows of purple prose, stood their ranks on her shelves: Oscar Wilde, Marcel Proust, Jean Cocteau, Ronald Firbank. Beaton’s works were inscribed, “To Reed and Diana…” Edith, Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell, the friends of her formative years, dedicate their essays in aesthetics on her title pages. Augustus Johns’ books are situated close by his pencil portrait of her…a gift.

As special consultant to the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum, Mrs. Vreeland invented a new approach to presenting fashion and the inspiration of her shows dominated the styles of the 1980s more than the influence of any single designer. Here on the shelves of her library, the histories of Hapsburg Vienna, Imperial China, Tsarist Russia, Belle Epoque France, Raj India, Edwardian England, and Grand Illusion Hollywood represent her inquisitions into each era. The Letters of Madame Sevigne, The Memoirs of Duc de Saint-Simone, Walpole’s correspondance, the Goncourt brothers journals, The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon — “I still keep it next to my bed. Meanderings of the mind, very charming. Little vignettes of wisdom and beauty”.

Three biographies of Maria of Rumania. A shelf of books on Edward’s abdication. Seven biographies of Diagilev, five of Nijinsky, four of Anna Pavlova, half a dozen on Leon Bakst’s designs for the Ballets-Russes. Misses Moberly and Jourdain’s Adventure, an account of two women of the twentieth century who step through a seam in time into the Trianon gardens of 1789 and there come upon figure after figure unaccountably arisen from that unfamiliar past.

All offered a clue to the modus operati that Mrs.Vreeland employed in mounting extravaganzas. History, in her mind, might be lived as fantastically as it can be grasped. “I think your imagination is your reality,” she’d say, “Only what you imagine is real. You love someone very much, but no one else sees her that way. But what’s the reality? Yours.”

The dining room is half walled with books – history, literature, and art – running the length of the room from floor to ceiling. Biography, photography and interior design are in the vestibule’s biblotheca. In the study are monographs on the great coutures: Poiret, Fortuny, Chanel, Schiaparelli, Dior, Balman, St. Laurant; treatise on fashion and rare books on costume. One of her favorites, reflecting a lifelong passion, is The Book of the Feet: A History of the Fashions of the Egyptians, Hebrews, Persians, Greeks and Romans, and the Prevailing Style Throughout Europe During the Middle Ages Down to the Present Period; also, Hints to the Last Makers, and Remedies for Corns, by J. Sparks Hull, Patent Elastic Boot Maker to Her Majesty the Queen, the Queen Dowager and the Queen of the Belgians. From the Second London Edition, with A History of Boots and Shoes in the United States, Biographical Sketches of Eminent Shoemakers and Crispin Anecdotes.

I spent nearly a week working on arranging the library, during which we became very good friends. After work she’d invite me to dinner and after dinner we’d sit up drinking Smirnoff’s neat with a twist and smoking Lucky Strikes. She’d sit in her little red child’s seat holding forth on the contemptible lack of quality in life today and the decadence of the modern novel — “The last novel I enjoyed was that one by Salinger” — or the sublime as effected by Henry James, George Eliot and Jane Austin, or the criticism she anticipated for the autobiography she and Chris were collaborating on: “Every word of it is real. How could I have made it up? I’m not all that imaginative, except in my mind.”

“Find me that bit in Polo’s Travels…marvelous,” she would drawl it out, “You know the passage..Elephants in all the regalia, walking six abreast through an ermine tent. Have you read that? Read it to me again. Ow, that’s turreiffirck,” she’d purr.

Jumel Terrace B&B

Jumel Terrace B&B Life Turns Man Up & Down

Life Turns Man Up & Down The Private Library

The Private Library