10 books on Art

There is nothing wrong with lists of 10 so long as they are disassociated with being the BEST of anything. I may get more requests than most for 10 Best Books, with admonitions NOT to think about it, from the inquiring minds of the internets, where a Zen-like preoccupation with the doctrine of no-mind predominates. Thinking up a list of 10 influential titles – on art, as in the list prefacing what I call auto-bibliography, is, as another compiler of literary lists called it, an exercise in style.

This was my 40th year a bookman, during which time I have handled an inordinate number of books. At home here in Harlem are 13,000 with varying purposes, detritus a variegated career, all significant. It is axiomatic to say that ‘one keeps old books as one keeps old friends’. They are the authorities we choose to align ourselves with.I would preface this list of influential readings on art with a brief word on the largest influence on my thinking about art. In 1974, when I started selling books, I was 21 and living in a storefront studio with my artist/musician friend Steve Kramer in South Minneapolis. I was a poet, by which I do not mean the kind that writes verses but the kind who is trying to establish some communication between ‘things’ and what J. Joyce referred to as ‘mayself’. We had come to a nasty existential impasse. Where I had found some consolation in the Word, Steven exemplified in primary experience how to brain up to Art; wherein ‘things’ and ‘self’ jell in what Lester Young called, “The Dance of Love” (Two to Tango). He taught me, God bless ‘im, Art is in the making. What you hang on the wall is what’s left over.

I have, ever since, found in art and poetry what others find in religion. In religion I find myself less and less Christian and more and more catholic.

1. Zen and Japanese Culture. D.T. Suzuki was my first favorite author. Just before I was kicked out of The Immaculate Heart of Mary’s 5th grade class, I was assigned to write about another religion and I chose Buddhism. In 1962 Zen was having an affair with Catholics interested in Liberation Theology. Noting the resonance between the Christian “ascetics of Coptic Egypt and the monks of early Buddhism in Japan, Thomas Merton sent D.T. Suzuki a copy of his Wisdom of the Desert: Some Sayings of the Desert Fathers (New Directions: 1960) and they were off and running.

Which resonated sufficiently so I found Suzuki’s Introduction to Zen Buddhism and Manuel of Zen Buddhism excellent introductions to the subject. If initially over my head, they made their way in. To find out what his beatitudes meant, I found Alan Watts’s The Way of Zen and a beat, forever linking Zen to the aesthetics of cool as I intuited it in 1966. Two years previous Merton and Suzuki actually met.

We met at the B. Dalton at Edina, Minnesota’s Southdale, “ the first indoor, multi-store shopping center in the US.”, where I would loiter while my mother shopped. B. Dalton, the first of the chain bookstores, was where I bought my first Evergreen and City Lights books. In ’68, when I was 16 and on drugs, fed up with ma’s trashy paperbacks, Ian Fleming Kyle Onstott, and Jacquline Suzanne, I escaped from suburban mall bookstores to Savran’s Books on the West Bank of the Mississippi in Downtown Minneapolis, where I discovered “the backlist,” Zen and Japanese Culture, and bohemian girls.

With it, I got with it. Nearby was the record store where I’d buy my first jazz records: Miles & Monk. Zen and Japanese Culture and Thelonious Monk posited themselves in stark contrast to the rising tide of vulgarity; a position I could measure things in relation to ‘mayself’ by. Like Monk, Zen’s substance and Suzuki’s style was clean, simple and laughed at the babbittries polluting the local culture, suggesting an attainable clarity, a state of grace, I’d experienced and wanted to recapture.

2. George Herriman’s Krazy Kat could have been what Andre Breton was thinking about when he remarked that what is surreal in Europe is real in America. An anomaly of early 20th C. pop culture, it’d come to my mid-century moderne attention in television animations.

We weren’t read to. We had cartoons in lieu of children’s literature. In the 1950s, local kid’s shows showed jazzy Betty Boops from the 1930s, wherein pretty white girls had reefer madness fun in urbane jungles. George Herriman, a Creole child of Jelly Roll Morton’s New Orleans, prefaced that visual jazz with something on a par with Louis Armstrong’s musical interpretation.

I have been deeply enamored, particularly since the 1977 edition from Grosset & Dunlap prefaced by e.e. cummings. Without Herriman what would cummings have been? What would Don Marquis have been? What would be a measure of his influence on Max Fleischer, S.J. Perelman, the Marx Brothers, and the other denizen’s of that American jazz underground that came out with Prohibition?

Herriman wore a hat near all his life so nobody’d know he had kinky hair, wrote in a jazz vernacular sometimes before the musicians, who read it in the funny papers, adapted to it, and, like them, smoked reefer. I got a buncha ideas about art from him. One of the principle being, it should fuck with your head.

3. The Banquet Years. Roger Shattuck had edited the infamous Evergreen Review, No. 13, the May/June issue of 1960, titled What Is ‘Pataphysics?, that changed my life in 1970. Hometown buddy James Aaron Crosby’d turned me on to acid years before and here we were on the down slide of hippie-dom in San Francisco, chumming around with a washed up alcoholic opera singer, Jeffrey, who hipped us to Alfred Jarry, Antonin Artaud and Jerzy Grotowski. After I read What Is ‘Pataphysics?, and was sold, I went on to Shattuck’s The Banquet Years toward educating myself. His overview of Belle Époque France’s avant-garde proved solid grounding in understanding “Modern Art” in a way previously incomprehensible. Art, as I’d suspected, could be lived.

4. The History of Surrealism by Maurice Nadeau is not a particularly good book but for a couple of generations it was the easily accessible affordable entry to the adolescence of modern art. Like cumming’s confessional Krazy Kat compendium, Nadeau’s book was a staple at the first book remainder store chains. In New York City, when I started selling books at the Strand in ’75, there were Marlboros that’d set up long tables in old shoe stores selling large folio Rembrandt, DaVinci & Michelangelo tomes, pleather sets of literary classics, Lyle Stuart reprints of middle-brow erotica, and cardboard paged children’s books that were never out of stock, amidst huge stacks of last years bestsellers and flops.

Every so often I get called in to help deal with the library of a deceased bibliophile who prided themselves on a bargain more than their housekeeping skills and I run into the same titles, inevitable shelved near steam-heat radiators and now decrepit. There are some keepers. My Krazy Kat still has the $1.00 sticker on it. I’ve sold my copy of Nadeau’s book several times over and don’t think I’ve ever been out of it.

It’s surreal.

5. The Dada Painter’s and Poets, edited by Robert Motherwell for George Wittenborn, the great mid-century midtown art book specialist. As dada may be superior to surrealism, this is a vastly superior book to the Nadeau. If nothing else, Dada was funnier. Both books were inordinately influential on my generation. Knowing these two books helped me suss out a good deal of the bullshit the New York art world thrives on.

6. Dialogues with Duchamp. I sometimes think Motherwell was a more interesting editor than painter. This is my favorite from his Documents of Modern Art, published by George Wittenborn from 1944-1972 and comprising sixteen indispensible titles to understanding what up with art in our time. What Is ‘Pataphysics? Pt. 2 by the consummate dandy. My favorite chapter: Eight Years of Swimming Lessons.

7. Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry. If you have to ask, and you do, Jacques Maritain is the man to ask. Read it when you’re in college or don’t, it’s as good.

8. The Flash of the Spirit. In 1983, Carl Lennertz, our Random House rep at Madison Avenue Bookshop, sent me a galley that would make the pieces I was puzzling over fall in place. I had been collecting the Onitsha Market Literature that’d make up my book, Life Turns Man Up and Down, for years before Robert Farris Thompson explained nearly all to me regards African aesthetics and their bearing on my world.

I themed our window on the book, executed it with Gene Moore. I’d made friends with some Yoruba guys who lived out in Coney Island who were selling me juju records and lent me one of the most beautiful gold robe imaginable and Gene, who did Tiffany’s windows as well, draped it over our near life-sized 17th C. Dutch articulated wooden figure as if it were out of the Ballet Russes. Perfection!

I asked to have Professor Thompson come by the shop to sign books and we have been fine friends ever since. Bob’s book not only defined aspects of the Black Atlantic that’d been on the tip of my tongue for years but was now firmly under foot in the East Village, where I was running in the fast company of the street school of art creating the creed of the time.

Uptown and outer borough guys Lee Quinones, Dondi, Futura, Fab and Jean Michel were representing and imaginary Africa downtown on subway cars, democratizing an increasingly academic art scene and challenging some tired ways of looking at the world. It was the upshot of a move for inclusion that’d started with the Black Arts Movement in the Greenwich Village and Harlem at the beginning of the ‘60s. Even Mr. Avant-garde, Andy Warhol, wouldn’t get to it until the mid-80s,and well-connected Henry Louis Gates wouldn’t prove until it was all over: We are all African.

They don’t get it. If you want to know why, and correct multiple misconceptions, read this book.

9. After I did I understood what I needed to understand to truly appreciate Art In Transit, my collaboration with Keith Haring, Tseng Kwong Chi, Dan Friedman and Henry Geldzahler the following year. The Flash of the Spirit animated our efforts. It was what I was talking about with Keith when we were working on his book. After living with Kramer this might have been the most intense art immersion of my life. Keith lived art like nobody’s business and died before it became all business.

10. Paintings in Proust is the last impressive book of connoisseurship to impress me. Literature is full of bad artists, those in Proust being notable exceptions. His ability to be in the moment of a painting is exemplary. Cinematic in his usage of stage, canvas and music, he proves doing a picture justice doesn’t often require a thousand words.

For the aficionado of his Remembrance Mr. Karpareles’ book is a joy. It is the birth of modernism through the eyes of one of its most perceptive interpreters. It is also one of my favorite books about anything. It’s impressive physicality enhances its study in a sensual way I’d think Himself would approve of. Likewise, the music in Proust makes a rewarding a study. It’s recommended for feeling up something as gratifying as his book.

A good read engages all the senses.

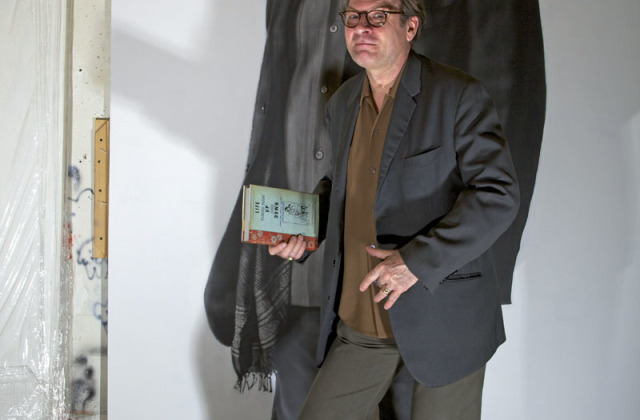

Photo & Painting by Curt Hoppe

Jumel Terrace B&B

Jumel Terrace B&B Life Turns Man Up & Down

Life Turns Man Up & Down The Private Library

The Private Library