Journeys of an Afro-Atlantic Envoy: With George Nelson Preston on Harlem Heights

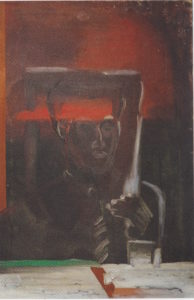

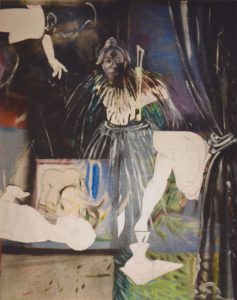

frontis: Forever Between Two Renaissances. Triptych from Tristes Tropiques/Sadly, the Tropics (2016)

The Museum of Art and Origins, 430 West 162nd St, NYC, NY 10032

The Museum of Art and Origins, 430 West 162nd St, NYC, NY 10032

As is our custom, I am having a twilight tea with the artist, poet, collector and scholar George Nelson Preston amidst the curated clutter of his home, studio and museum on West 162nd St. The Museum of Art and Origins is the New York branch of Rio de Janeiro’s Museu de Arte e Origins. Both collections are shrines to his Afro-Atlantic ancestors and life’s works.

Recently he’s had a retrospective of his paintings from 1954 to the present at the Wilmer Jennings Gallery of Kenkeleba House, an East Village gallery long devoted to that neighborhood’s Afro-Latino artists off Avenue B. In 1958 twenty-year old George left our Uptown neighborhood for what he refers to as The Scene, currently the subject of Inventing Downtown: Artist Run Galleries in New York City, 1952-1965 at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery on Washington Square.

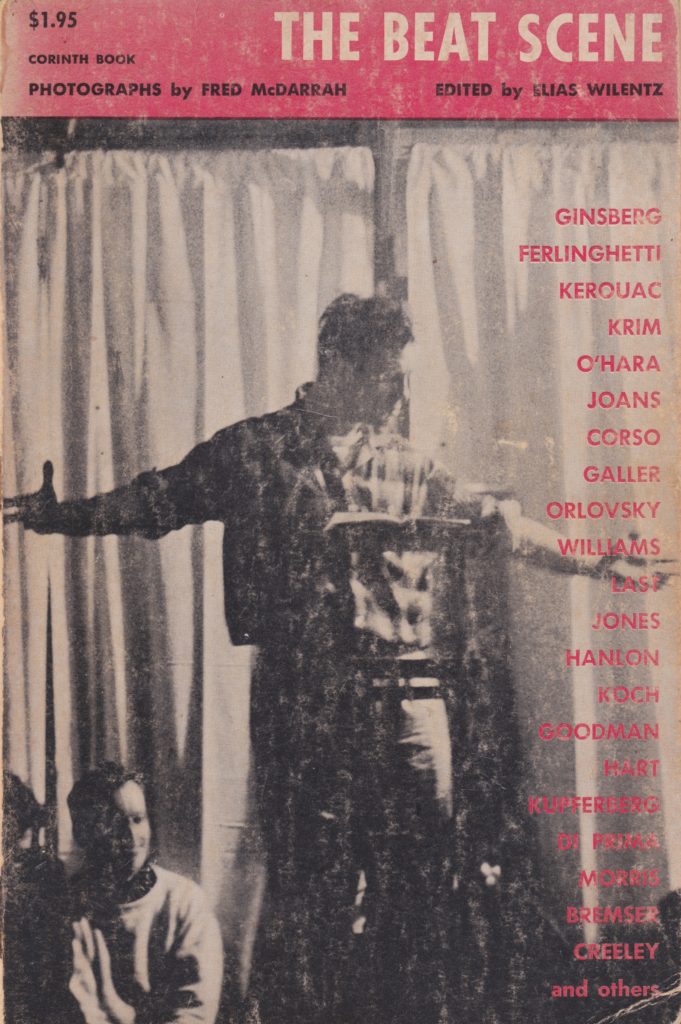

Featured in Village Voice photographer Fred McDarrah’s contemporary chronicles The Beat Scene and The Artist’s World in Pictures, George’s East 3rd St. live-in storefront jazz/art/poetry gallery, The Artist’s Studio, introduced me to him, in cinematic paperback black & white, decades before we met. Therein, Jack Kerouac. in sleazy flannel, holds an audience including my teenage heroes, Allen Ginsburg, LeRoi Jones, Gregory Corso, and Ted Jones, with a chorus of spoken blues. Oldenberg’s premiere paper mache hamburger in the window of The Store next door solicited a neighborly, “Claus, da fuck’s this?,” to which the sculptor might have replied “Pop Art” had the term been coined. With Red Grooms and Jay Milder he groomed City Gallery – one of Chelsea’s first.

In his late 70s, he retains both a bohemian and athletic stature. His features resemble those of the Akan of Eastern Ghana who became the focus of his studies on quitting The Scene. The Journey goes something like this: from Renaissance Harlem to swinging Greenwich Village, to Revolutionary Cuba, back Uptown to birth The Black Arts Movement with Dr. Kenneth Clark’s Haryou and to study with the founding fathers of Black Studies, off to Ghana, and back home to Harlem, where his mother introduced us thirteen years ago. In tandem with his opening his home as a museum I opened mine, two short blocks away, as a bookshop on the same subjects.

I asked him about his trajectory:

Preston: This house started in 1776 when Col. Preston of the Continental Army bought six “strong Virginia negroes” in exchange for 600 acres of land. That’s where Preston comes from, OK? In the 1830s my mother’s ancestors, who were free by that time, were the founders with the Smalls – I’m talking about the Smalls who captures that Confederate gunboat – of Liberty Hill in North Charleston. They came up here, to Harlem, my mother’s ancestors, by boat around 1918 and worked as domestics. My mother described it as “Spying on white people.” What do they do? They send their kids to museums so so did my grandmother. She didn’t know anything about museums but she took my mother to the museum.

Interviewer: And now you live in one.

Preston: In the early ‘90s I participated in a collaboration with Dr. Dinah Papi Guimaraens and Heloísa Aleixo Lustosa of the Museo National de Belas Artes in Rio de Janeiro. The museum at that time was oriented to classical European painting, a lot of it not all that good. The idea was a museum that represented the unrepresented of Brazil, that the authenticity and the natural integrity of the Brazilian African and Indian’s work merited not just being shown in some ethnographic museum but in an art museum.

Interviewer: How from that concept in Brazil to this in Harlem?

Preston: I started with a simple shrine to the memory of my ancestors. Their photographs shared an altar with mementos of the Afro-Atlantic journeys my works chronicle. Now the entire house is my shrine, an homage combining these ancestral photographs, the African art I’ve collected and my work. For instance, beneath this Malinke mask is a photograph of my maternal grandmother and a Santero fly whisk my son acquired in Cuba two years ago. My mother, who sits at the center of the alter, is why we’re sitting here.

Interviewer: An artist’s collecting – not all artists collect – can be integral to their aesthetic practice. While predominately sub-Sahara African, your collection includes Egyptian, Renaissance European, Baroque Brazilian, Native and African American traditional and contemporary art – all of which influence your paintings. Could you tell us something about your style of collecting?

Preston: Collecting is both a love of art and a conceit. You’re not only collecting because you love art compulsively but everything you collect is an expression of your aesthetic judgment, your taste. Now, you have the taste l’air du temps, the prevailing taste of the time, and then you have particular tastes and canons. For a long time there was a French canon that dominated the collecting of African art and it favored objects that closely related to the marble sculpture of our Western traditions.

For example, tribal art such as that of the Baule of the southern Ivory Coast. Much of their art is highly refined, with the smooth, polished surfaces that dominated the French dealers taste. The first piece I acquired was just such a Baule piece from Merton Simpson in January of 1967. But one of the ways that I’ve been a successful collector is that I didn’t pay any attention to the au courant dealer’s taste. Simpson, the first successful black American dealer (eventually lauded as “Numero Uno” in The Connoisseur) had both conventional and against the grain taste. Picasso and Picabia were collecting very gritty, very funky stuff covered with sacrificial blood, encrustations of eggs, the feathers and remains of the chickens that have been sacrificed over them, because they felt that the unlikely combinations of materials that the Africans were using had some affinity to Surrealism, to them, and that’s what interested me. Early European collectors had been removing those non permanent materials that ‘distracted from the smooth surfaces of the ‘permanent’ wood.

For example, tribal art such as that of the Baule of the southern Ivory Coast. Much of their art is highly refined, with the smooth, polished surfaces that dominated the French dealers taste. The first piece I acquired was just such a Baule piece from Merton Simpson in January of 1967. But one of the ways that I’ve been a successful collector is that I didn’t pay any attention to the au courant dealer’s taste. Simpson, the first successful black American dealer (eventually lauded as “Numero Uno” in The Connoisseur) had both conventional and against the grain taste. Picasso and Picabia were collecting very gritty, very funky stuff covered with sacrificial blood, encrustations of eggs, the feathers and remains of the chickens that have been sacrificed over them, because they felt that the unlikely combinations of materials that the Africans were using had some affinity to Surrealism, to them, and that’s what interested me. Early European collectors had been removing those non permanent materials that ‘distracted from the smooth surfaces of the ‘permanent’ wood.

Interviewer: And in the last three decades they’ve looked beyond that slick surface to the deep story and spirituality of the work?

Preston: Yes, because the historical/cultural narrative of African art was what I call ‘defoliated’ with the removal of the costumes, feathers, sacrificial patinas, etc. that had been removed to reveal the ‘pure’ carved wood forms. But Western artists and scholars came to understand, that their own quest for innovative formal meaning depended on the integration, adaptation and appropriation of these African incongruities. Many African peoples produce art just like we do, in a variety of formal expressions. media and emotional ranges from very cool contemplative ideals to very forceful, very aggressive forms.

Look at this piece from Nok: Nigeria, 500 BC. What was happening in Greece in 500 BC? They were transitioning into their pre-classic on which Egyptian art had an influence. Egypt at that time was already two thousand years old. Coevally, in 500 BCE Nigeria there were extensive trade networks ranging north past Timbuktu and south beyond Angola. We know that by archeologically examining the tools, the implements, the types of jewelry and clothing that are depicted on these statues.

Interviewer: How many pieces are in your collection?

Preston: Just over five hundred. And you know why a lot of this work is here? Because Africans bring it here and sell it to me because they’d rather do that than be humiliated by the dealers. I’m regarded as their chief in New York. They all call me Nana, whether they’re from Mali, Guinea or Ghana.

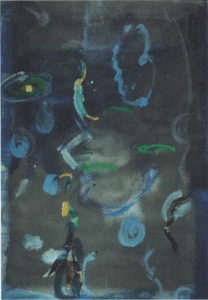

You can see the influence of African iconography in my paintings. But let’s talk of how I fit in with an aspect of Western formal ideas. Black in Western pictorial spacial illusionism has the optical property of receding but mine is a translucent black that doesn’t stay still because of its light parts. And then there’s this layer of leafy forms and they appear to be cut into the black – a particular form that has to do with historical consequences of defoliation of forest and culture / raw and cooked.

You can see the influence of African iconography in my paintings. But let’s talk of how I fit in with an aspect of Western formal ideas. Black in Western pictorial spacial illusionism has the optical property of receding but mine is a translucent black that doesn’t stay still because of its light parts. And then there’s this layer of leafy forms and they appear to be cut into the black – a particular form that has to do with historical consequences of defoliation of forest and culture / the raw and cooked.

Historic Sea Lanes of the Slave Trade: Matanzas at Nightfall (1962)

Historic Sea Lanes of the Slave Trade: Matanzas at Nightfall (1962)

At the time I’m already dissolving the distinction between the frame, the field and the figure in my painting. At that time Meyer Shapiro isolated the different stylistic regions of what he called “Insular Medieval Art”, the illuminated manuscripts of the British Isles, wherein he notices that he could differentiate the art of each monastery by it’s unique approach to form, field and figure: classic style analysis.

Interviewer: It’s interesting how the artistic criteria you establish in the 50s downtown is reinforced by your academic studies and fieldwork in African art. You and your fellow artists in Grey Art Gallery’s current exhibition, [Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952-1965] presage these scholarly distinctions. While the continuity remains, the concepts achieve new depths and provoke change.

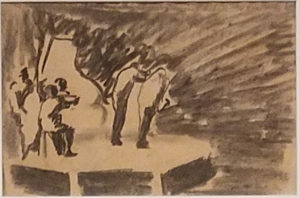

Preston: In the 50s and early 60s I wasn’t yet thinking of African art. I was thinking about Japanese ukiyo-e’s influence on edges in Impressionist art, Degas for example. Here we see figures that previously would have been contained in the frame are cut off. I thought about not only what’s inside the frame but the formal and narrative meaning behind the canvas and what’s happening between the painter behind and the viewer in front of the picture.

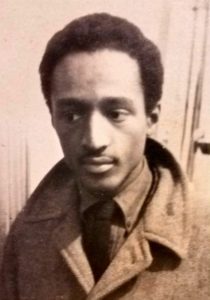

Self Portrait on a Picture Plane (1959). From the collection of Henry Taylor.

Self Portrait on a Picture Plane (1959). From the collection of Henry Taylor.

Self portrait. George Nelson Preston, 21 in 1959

Self portrait. George Nelson Preston, 21 in 1959

Where do our perceptions come from? To me there is a mysterious spiritual entity behind everything, like in the transcendentalist poets who placed intuitive subjectivity over empiricism. It’s the idea of the intuitive sense of the beyond and the spiritual in art being more important than its tangibility.

So how to create a painting that has that spiritual impact, a painting that when you look at it creates subjective feelings that take you beyond that painting? One that doesn’t accept just representing something I’ve seen or thought but gets after the Great Spirit behind it all, that transcends the identity of the painting beyond both painting and object so that it becomes metaphysical? I’ve always been attracted to these transcendentalist artists, like Arthur Dove. O’Keefe is like that. You look at that work and you always sense something beyond those lilies. You think of this enormous spiritual, mysterious entity.

Interviewer: Which you end up pursuing by other means when, in ’64, you leave the art scene without leaving art. Were there artists among your contemporaries you felt a kinship in this?

Preston: The attraction of the 10th St/New York School movement was its diversity. You didn’t have to be connected to certain people or galleries or to museums or to society. You didn’t have to have any of those connections that the Art Mafia operate on. There were artist -run galleries and if the other artists in the gallery felt that your presence was equal to their professionalism and enhanced it you had an opportunity to show. That was the attraction.

Art Blakey and His Jazz Messengers at the Five Spot (1959).

Art Blakey and His Jazz Messengers at the Five Spot (1959).

There’s been a rebirth of Downtown but the forces that control the art world are occupying that space now. Very few of those galleries are artist formed cooperatives. 10th Street ran out of steam because the artists who created it were pursued by the galleries Uptown. They’d created Downtown as an alternative but when they had the opportunity to make some money naturally they moved on up to the East Side.

Phoenix Gallery, that represented me, moved uptown and is still there but what we were doing has been replaced by these theory driven –isms dealers use to market art. You have to paint this, you have to do that, it must be flat, you should use only colors that do x, y, and z, and on and on it went with the –isms. There are more of these –isms that have replaced each other between 1955 and 1985 than in the entire history of Western Art. Look how long First Style Renaissance was an –ism until it changed to Second Style and look how long Mannerism and the Baroque and all these periods lasted. Then between ’55 and ’85, Abstract Expressionism, Figurative Expressionism, Pop Art, Op Art, Color Field Art, Minimalism, Neo-, Post-, and on and on. You see what I’m saying?

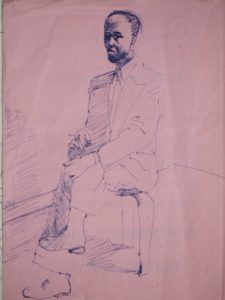

Portrait of Norman Lewis (1984)

Portrait of Norman Lewis (1984)

What I observed was that however much the Downtown artists work looked like whatever was in vogue Uptown it was not theory driven. I mean, Mel Edwards was working in direct metal and direct metal was not intended to be evocative and Edwards work is historically evocative. A lot of it refers to the history of slavery. You have these black artists working at the time, Norman Lewis, Bob Thompson, Romaire Bearden, all at the Spiral Galley. They had a lot of style, different styles, not theories.

Interviewer: Was there a commonality among these artists?

Preston: What black artists had in common was that they were least likely to be sponsored by the Art Mafia. At that time the Art Mafia was still trying to give audiences the impression that black artists told narratives about black life. Basically that black artists were not working within the current vocabularies. Which was not true. One of the things Bob Thompson, Bearden and I had in common was this Afro-Atlantic voice, the use of Western art history, jazz, and Africa.

There’s this double-consciousness of the West and the rest. The West is restless. The West is never satisfied with itself. As soon as it discovers an –ism it becomes the beast that devours that –ism, the child that wants to kill the father. That’s the restlessness in it. As soon as you get one -ism, an artist’s supposed to be in dialogue with it, framed by it.

African art is not contained in a frame or an imaginary frame. In what I call the Museum Aesthetic, the isolation of African Art objects as solitary forms, put in a spotlight that speaks to the aesthetic and savvy of the curator more than to the context in which African art is to be seen. When I did my exhibitio\ Sets, Series and Ensembles in 1985, I showed African art not in this Museum Aesthetic. I showed the sets of objects, the ensembles of objects, and the series in which they would appear on special occasions or even over years and how the art was exhibited like that, unframed.

African art is not contained in a frame or an imaginary frame. In what I call the Museum Aesthetic, the isolation of African Art objects as solitary forms, put in a spotlight that speaks to the aesthetic and savvy of the curator more than to the context in which African art is to be seen. When I did my exhibitio\ Sets, Series and Ensembles in 1985, I showed African art not in this Museum Aesthetic. I showed the sets of objects, the ensembles of objects, and the series in which they would appear on special occasions or even over years and how the art was exhibited like that, unframed.

Interviewer: And functioning within a spiritual context of ceremony, ritual, and performance.

Preston: Most African masks are creatures of the forest, the bush, and the bush is nature, and the human beings have to offend nature in order to create civilization. You have to cut down trees, you have to kill what’s green, or else we can’t live. So there’s an existential contradiction there. When African masks perform they don’t come out of somebody’s house. They are sequestered in the forest and they come out of the forest. They have to be coaxed out of the forest and into the village. Now how do you frame that? How do you put that into Museum Aesthetic? That had a great influence on me.

When I was new in Mamfe they took me to a sacred place, a spring, and I was told the people who were there before the Akan sent out pathfinders to find water and they found that spring. And it’s a very strange spring because it’s almost shaped like a perfect box. The stratified stone, at Kwadwuo Kwaye, it’s like a vault. In the Akan mind God is impossible to illustrate because how could someone know what God looks like? But God manifests itself in tangible form, masculine water and feminine earth and they say, “Except the Spirit of the Sea. Fear Nothing.”

So, fearing nothing, I attempted to manifest His spirit in my Triptych from Journeys of an Afro-Atlantic Envoy. The panel on the left, I Saw the Scepters of Lord Topre By the Spring Called Kwadwuo Kwaye in the Bush near Akuapem-Mamfe (Ghana), is my evocation of the darkness in the forest at that spring. The panel at the center, Then I saw the Scepters of Lord River Densu is autobiographical. Now the amazing thing is when I was consecrated as a chief I had to take one of these swords, hold it upside down with the handle pointed at all these elders and the Chief of that region and swear, “I swear, I swear, I swear. If you need anything that I’ll be there.”

Triptych from Journeys of an Afro-Atlantic Envoy (2006).

What interests me about the third panel, In the Forest of the Kilombo of Zumbi of Palmeiras, is the force behind this. So the reason for that black darkness and the transparency of it is that I’m hoping to create a certain inexplicableness. You know, we don’t know what God looks like. A certain inexplicableness that’s behind the picture is coming out. [Note the ceremonial scepter GNP is holding is both in the picture within that picture and the scepter on the right in I Saw the Scepters of Lord Topre]

Renato Da Silva Araüjo, the chief researcher at the Museo Afro-Brazil, points out that I’ve attempted to use form as a historical narrative. This is different from picture story telling in historical paintings, where they try to find that critical moment in history and then doing a painting of it; General Wolfe dying at the Battle of Quebec, Washington crossing the Delaware. I don’t do pictures like that but I attempt to use concepts such as defoliation, depicted in the falling and accumulating leaf like patterns that I use as a metaphor for the defoliation of the rain forest, the defoliation of Afro-Atlantic culture, the defoliation of the Amazon because all tradition is associated with a geographic physical place.

Why do the Israeli conservatives want to usurp Jerusalem? Because the Temple Mount is there. But it’s also a Christian and Islamic shrine. If they usurp it they destroy it for others. So destroying the rain forest, defoliating it, is the same thing as Islam and Christianity coming into areas and desecrating, destroying, stripping the leaves away, because without leaves there’s no response to the sun and without photosynthesis a tree doesn’t grow. If you destroy the Black Hills you destroy the earth where everything originates.

Why do the Israeli conservatives want to usurp Jerusalem? Because the Temple Mount is there. But it’s also a Christian and Islamic shrine. If they usurp it they destroy it for others. So destroying the rain forest, defoliating it, is the same thing as Islam and Christianity coming into areas and desecrating, destroying, stripping the leaves away, because without leaves there’s no response to the sun and without photosynthesis a tree doesn’t grow. If you destroy the Black Hills you destroy the earth where everything originates.

Interviewer: Would you extend this to the defoliation of Harlem?

Preston: It’s the same thing. It is the denuding. 125th St. is being stripped of what originally were individual temples of black expression. Those guys out there selling incense and oils have a particular meaning in African American culture. If you start putting up chain stores and saying, “You can’t have this stall out here,” you see what you’re doing? People moving into high rises built opposite Marcus Garvey Park and then telling the drummers, who have been meeting there for decades, that they’re making too much noise. This is all the defoliation. This is all the melting of the ice cap. This is the destruction of the environment and replacing it with something that has no continuity. Once that ice breaks off there’s no continuity between that and what’s left. You put those high-rises up and tell those drummers to go away, what continuity does that high-rise represent?

Interviewer: And in the broken continuity we have the end of civilization as we’ve known it?

Preston: We have to be like jazz. Constantly innovating. We have to be constantly trading fours, we have to be constantly riffing, and we have to be constantly quoting some tune or some melody that came before us because jazz is resiliency. That’s what represents the continuity. In these other forms, from pre-bop to hip-hop, everything is related to something that came before it. But the different stages in jazz are the continuities. It is playing yesterday, today, tomorrow and beyond. When we hear jazz we know there’s a beyond after today. I’ve got to do my work to remind people that this is not the end.

Sacrificial enstoolment of Nana Anakwa, Kyidom Aboafohene of Akuapem-Mamfe.

Sacrificial enstoolment of Nana Anakwa, Kyidom Aboafohene of Akuapem-Mamfe.

Photo: Petra Richterova, 2001

Thometz & Preston. Aaron Burr’s birthday.

Partial text published in Ubikwist #4, Spring, 2017

Photos by Frank Stewart & Kurt Thometz.

Addendum: from

pg. 138-9: “One night a not entirely blameless Dick found himself on the receiving end of inner-city road rage when he boxed in the car parked in front of his. His own decrepit vehicle, its make unremembered, was one in a string of similar wrecks he would drive in the course of a lifetime. On this particular evening he drove Sheindi and Stella to a party hosted by George Preston, a young painter and poet who showed at the Phoenix Gallery, a Tenth Street co-op. Preston lived in a storefront apartment at 48 East Third Street, where he hosted readings attended by people like Norman Mailer, Paddy Cheyefsky, Elizabeth Taylor, and Eddie Fisher. A photo of Preston’s salon is the cover image of Fred and Gloria McDarrah’s book on the Beat Generation’s ” glory days” attesting to its importance for the “Scene,” a movable party that formed itself wherever the action was that evening.

Dick, Sheindi, and Stella had just settled back into his jalopy after leaving Preston’s party when the driver of the trapped car and his friends sprang at them and began to smash Dick’s windows with baseball bats and paving bricks. Stella pushed Sheindi’s head below the dashboard to shield her as the glass shattered. By the time Dick thought to scare them off by leaning on the horn, his car was totaled. Preston long remembered Dick trooping back inside to report his loss “very un-materialistically.” Preston understood that “people like us were mysterious, enviable, and disquieting to the local people on the Lower East Side.”

Dick, Sheindi, and Stella had just settled back into his jalopy after leaving Preston’s party when the driver of the trapped car and his friends sprang at them and began to smash Dick’s windows with baseball bats and paving bricks. Stella pushed Sheindi’s head below the dashboard to shield her as the glass shattered. By the time Dick thought to scare them off by leaning on the horn, his car was totaled. Preston long remembered Dick trooping back inside to report his loss “very un-materialistically.” Preston understood that “people like us were mysterious, enviable, and disquieting to the local people on the Lower East Side.”

“People like us” meant Beat and multiracial. Preston was one of several African American writers and artists in Dick and Sheindi’s circle. They knew LeRoi Jones, the future Amiri Baraka, then married to the writer Hettie Jones, who was Jewish, and the figurative expressionist Emilio Cruz, who lived with Sheindi’s close friend, the dancer June Ekman, just across East Broadway. The innovative abstract expressionist Ed Clark, one of the first painters to experiment with asymmetrically shaped canvases, had a day job at the Sidney Janis Gallery. When Dick needed names for the Green’s first mailing list, Clark helpfully passed along a copy of his boss’s list.”

Jumel Terrace B&B

Jumel Terrace B&B Life Turns Man Up & Down

Life Turns Man Up & Down The Private Library

The Private Library

Kurt–this is a great interview. Each time you take the time to do these, you grow another leaf somewhere that adds oxygen to our survival. Thank you. I am sharing.

Terrific and insightful interview. Among the issues discussed, I was quite taken with the “defoliation of Harlem,” which is an issue that underscores the term ‘gentrification.’ I look forward to more such interviews.