Private Libraries Make Novel Use of Booksellers (including me).

Posted by KT on Thursday, March 8, 2018 · Leave a Comment

How to assemble a bespoke collection for the home.

by Emily Rhodes. From the Financial Times, March 10, 2018:

The Duke of Devonshire’s library at Chatsworth House © Paul Barker, reproduced by permission of Chatsworth House Trust.

“A library is your story on a shelf,” says Nicky Dunne, manager of Heywood Hill, the London bookshop where Nancy Mitford used to work. He has walked me through the cold bustle of Mayfair, past the impressive fronts of town houses, offices and clubs, ushered me inside a grand residence, and then, all of a sudden, we are cloistered in a beautiful private library. Our feet are muffled by the soft Persian carpet, our eyes feast on the rare books that fill the handsome bookcases against the walls, and as we sit down I notice that the clock on the mantelpiece has stopped; we have entered a time apart. If a library is a reflection of its owner, then it soon becomes clear that the overriding narrative here is a passion for travel and scholarship between east and west. Dunne specialises in creating bespoke libraries for clients, based on their interests — be that 250 books on “the great American novel” for a study wall in a second home in California, 2,000 “books to help diplomats understand Britain” for the London embassy of an Arab government, or 1,500 books “to tell the positive story of humanity across the arts and sciences” for a French client.

The curiosities of bibliophiles are certainly wide-ranging. Norfolk-based Noel Bolingbroke-Kent gave me a list of subjects for libraries he’s formed over his 30-year career that ranges from British canals to Islamic art, via foxhunting, falconry and the French diplomat Talleyrand. “Curating libraries is a natural extension of our way of bookselling,” explains Nic Bottomley, owner of Mr B’s Reading Emporium, an independent bookshop in Bath which offers “reading spas” and “reading subscriptions”. “We are used to customers coming into the shop with all sorts of bizarre requests: books on medieval archery, books on cannibalism . . . Actually the funny thing is that cannibalism is quite common in 20th-century fiction — we found that lady a whole bundle.” Recently, he found 400 books for a local IT consultancy: the owner wanted a library to inspire his employees with books focusing on entrepreneurship and “creative thinking around business”.

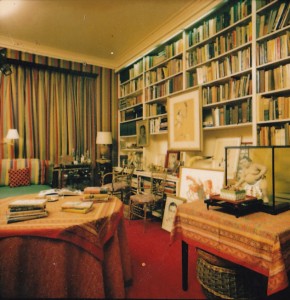

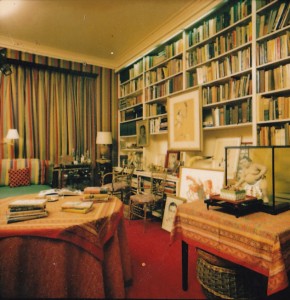

Private library in Switzerland selected by Heywood Hill © Marc van Swoll.

Nicky Dunne of Heywood Hill © Benjamin McMahon

Quirky interests aside, Pom Harrington, owner of Peter Harrington Rare Books, suggests that people tend to have “a romantic notion of what a library should be”: essentially a book-lined room where you can sit down and pick up a classic. To this end, he suggests purchasing “library sets” — handsome collected editions of classic literature, smartly bound, but without quite such an eye-watering price tag as rare editions. A five-volume set of Jane Austen’s novels, for instance, would set you back around £1,500 as opposed to £10,000 for a second edition of Pride and Prejudice. On a budget, and for a huge room, he suggests cheating and filling the high shelves with leather-bound law journals, which look the part from a distance and are much cheaper, at about £1,500 for three metres. Harrington points out that “it is actually quite hard to spend more than a few thousand pounds on a book. The choice can be between buying just one significant painting, or an entire library”.

“Books are more engaging than a piece of art,” says Kurt Thometz, a private librarian based in New York. He reminisces about “the go-go 80s”, when working with fashion editor Diana Vreeland led to his services being called on by Brooke Astor and other American socialites. He speaks fondly of his relationship with his clients and how, in working with their collections, he “got to know the best side of them”.

Perhaps a library can be a means of showing off this best side of ourselves, putting it on the shelves for all to see, but it can also be “deeply personal and not ostentatious”, argues Harrington, mentioning one client who housed his most special books in unlabelled plain boxes, and another for whom he amassed 300 books with fore-edge painting, a feature in which a scene is painted across the edge of a book’s pages and revealed only when the pages are fanned out. London and Shropshire-based interior designer Rupert Bevan is sensitive to these twin poles of a library’s potential function: “It can be used for display, or for storage; it can be a space to entertain or a space to hide away.” He first tries “to get a feel for why a client wants something” and works out the design accordingly. He gives the example of a mathematician who wanted to house 27,000 books about cricket. To meet the challenge of fitting so many books into the given space, Bevan designed hinged shelves to store less important books within. He also created a lockable cabinet to display and protect the more valuable books, and several low units that can be wheeled together to create a large dining table for charity functions, as well as holding books.

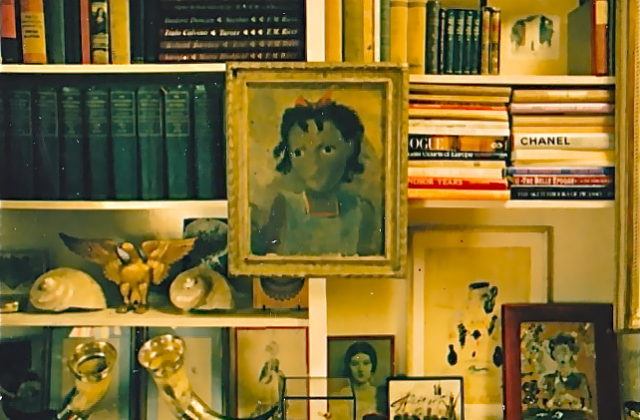

Diana Vreeland’s library at her Park Avenue home © Tsung Kwong Chi.

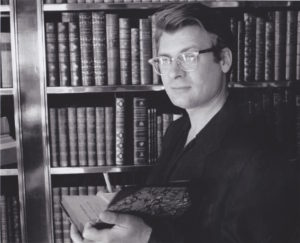

Kurt Thometz in Brooke Astor’s library, which he curated © NYTimes. (circa 1988)

In terms of scale, Dunne and Harrington agree that a library can stretch from just a few books meaningfully assembled, to metres of wall space, to an entire room. Architect-trained interior designer Daniel Goldberg at London studio State of Craft compares books to fireplaces in the warmth they bring to a room. He also recognises “the rich tradition of the English country house library” and recently designed one for a new-build. Goldberg and his colleague Thomas Daviet talk thoughtfully about the “ritual” of a library and how they tried to create an appropriate feeling through material and furniture. They designed reading tables with surfaces of parchment and leather, in part to protect the books, but moreover so that the softness would foster quiet contemplation. They also consider more prosaic matters, such as the colour and height of the books: when they designed a library with travertine bookshelves, they sourced a particular collection of Churchill’s diaries with a binding to complement the hue of the stone. On the subject of shelves, Harrington says he would always advise getting adjustable ones, as a library “can evolve as the owner’s interests change or deepen”. Nonetheless, Bevan tells me that although most of his clients ask for adjustable shelves, very few end up actually adjusting them. Maybe this is due to not overfilling the library at the start, rather than our innate inflexibility. Dunne recommends filling around 70-80 per cent of the space and allowing the library’s contents to expand gradually over time. Bottomley often tops up his libraries with new releases over the coming months.

Library designed by Rupert Bevan © Rupert Bevan

Early edition of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary © State of Craft

What happens when a library comes to the end of its life, as could happen when downsizing, or following its owner’s death? Some private librarians will take on a whole collection. Kinsey Marable, an American who became a bookseller after a spell at Goldman Sachs, buys entire libraries, repackages them and then sells them on, in what he calls “a Wall Street practice” of turning a profit. Heywood Hill finds new homes for existing libraries as a way of keeping a special collection intact rather than splitting it up at the auction house. Dunne is currently looking after three formed collections — I met him in the musty midst of one of them. If a library is “your story on a shelf”, then passing it on to a new lover of books is a neat way to avoid writing the end, and begin a new chapter instead.

Travertine shelving © State of Craft

Tech and Tomes

Pom Harrington may say that it’s not easy to spend more than a few thousand pounds on a book, writes Fergus Peace. Tech billionaires, though, will find a way. While their innovations promise permanent and infinite information, some of the great men of digital technology prefer fragile bundles of paper for themselves.

Mark Zuckerberg said as much in 2015, when he ran a year-long online book club. “Books allow you to fully explore a topic and immerse yourself in a deeper way than most media today,” he wrote in an apparently irony-free Facebook post. Some 700,000 users followed his “A Year of Books” page.

Elon Musk, who launched a sports car into space last month, reportedly taught himself rocket science by reading borrowed textbooks. In 2016, a mention by him in an interview of Twelve Against the Gods, an out-of-print history book from 1929, caused its price on Amazon to rocket from just $6 to $99.99.

These new iconoclasts are following a well-trodden path. In 1994, Bill Gates paid $30.8m for the Codex Leicester, a 72-page manuscript of notes, sketches and diagrams by Leonardo da Vinci — at the time it was the most ever paid for a book. There has, though, been some return on the investment: several pages of the Codex Leicester were used in a Da Vinci screensaver for Windows 98.

Gates’ Microsoft co-founder, Paul Allen, seems to lack such a keen commercial eye. The copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio he bought in 2001 for more than $6m hasn’t featured in any business ventures. It is, at least, in the hands of a real fan. Allen’s foundation has donated more than $11m to the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, and he has even lent the Folio to the festival for educational events.

The Codex Leicester will be on loan to the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, from October 29 to January 20 2019, uffizi.it

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2018. All rights reserved.

The Duke of Devonshire’s library at Chatsworth House © Paul Barker, reproduced by permission of Chatsworth House Trust.

The Duke of Devonshire’s library at Chatsworth House © Paul Barker, reproduced by permission of Chatsworth House Trust.

Jumel Terrace B&B

Jumel Terrace B&B Life Turns Man Up & Down

Life Turns Man Up & Down The Private Library

The Private Library